|

As the testing life cycle has matured and test techniques

have developed, new test engineers and test managers

have to acquire additional knowledge of the test domain.

Since testing is more than simply a phase of the software

development life cycle, people performing the test

engineering and test manager functions must be aware

of this fact. We must become salespeople of a sort,

to transfer this knowledge to our executive management.

If we don't have this knowledge ourselves, we won't

be very good at the sales part of the job.

But, if you as a new test engineer or a new test manager haven't spent

years in the field, how do you know what to sell? As an example, the key to developing

a good test program is a good test plan, and the key to developing a good test

plan is a good set of requirements. There is a variety of literature that discusses

techniques for generating good requirements, but there are a lot of very talented

software development engineers and test engineers who have never read any of that

literature. The situation relative to executive management is even worse. We test

engineers should be stressing the need for good requirements development to the

development and management communities. We can do this in three ways: by encouraging

requirements reviews, by reviewing requirements testability using a simple technique,

and by developing test plans. How do you know that this is something you

should be doing? You could spend a year attending testing conferences sponsored

by a variety of organizations; two of the best are the Quality Assurance Institute's

International Conferences on Software Testing and Software Quality Engineering's

STAR Conferences. Or, you could read the IEEE Software Engineering Standards from

cover to cover (note that, currently, this is a four-volume set). Alternatively,

if there were one concise roadmap of the tasks a mature test engineering organization

can and should be performing, it would assist in identifying these tasks. I submit

to you, that if you become acquainted with the process model described in this

book, you have this roadmap in your hands. In brief, what I am providing

in this book is a list of tasks and processes for a program of formal testing.

If you are just starting to implement a testing process, you will not want to

try to implement all parts of this model in one fell swoop; it would be too overwhelming

and too costly. In later chapters, I suggest ways to implement this process in

a prioritized, piecewise fashion. Cooperation Between

Testers and Developers It is worth noting that as test engineering

has matured since the early 1970's, we have realized that we do our best work

in an environment where there is no longer an adversarial relationship between

the people doing software development and those folks performing the role of test

engineering. We are all part of one organization, and our overriding goal is to

produce the best possible systems and software for our customers, given the constraints

of resources and time. One of the reasons for reviewing requirements and

addressing testability of those requirements early in the life cycle is to make

testing easier, but testable requirements will also make design and coding easier

for software development. If requirements are so ambiguous that test engineers

don't know what to test, how can developers be expected to design and code to

those requirements? In contrast to some of my contemporaries, I have always

tried to encourage complete and open communication between a test team and a development

team. Software development personnel should be reviewing test documentation, in

the same way that test engineers review requirements, design, and code. Early

and frequent feedback between the various groups on a program will contribute

to lower costs and faster time-to-market. There should be no surprises in the

test documentation for development staff members, since they should have thoroughly

reviewed these products. How to Use the

Formal Testing Process Model There is no "one true way" to test

software, so the goal of this book is to provide you with a structure and set

of best practices that you can use to develop a formal testing process that fits

your needs, and those of your customers, your management, and your organization.

You should consider this book as a menu of things you could do, and then establish

a set of priorities for what you'll do first, what you'll do second, and so on.

As an example, suppose you are working in a test engineering role in a company

in which the current practice is that when executive management gets an idea for

a new application to add to the software suite your company produces, the following

happens: First, management assigns a developer to the task; then, the developer

takes the limited input from management and writes code for the application. Thus,

in such an environment, the entire requirements and design process is minimized

at best, and short-circuited at worst. When code is complete, as far as the developer

is concerned (and we'll believe that he or she did some limited unit testing based

on an understanding of the "requirements"), the developer hands the

code to the test engineer he or she is most comfortable working with, or to the

team leader of testing. This may well be the first time that the folks involved

in testing have heard about this new or upgraded application. If you're

in the role of testing team leader or test engineer, what good does the model

in this book do you? In this specific instance, I'd advise you to look carefully

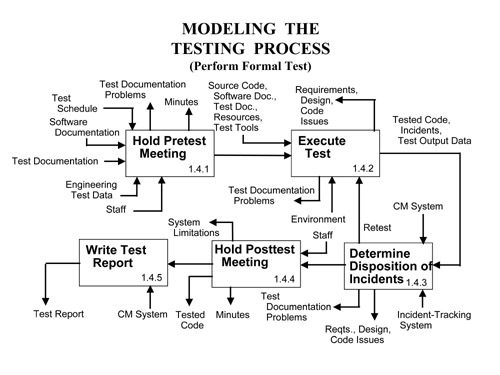

at the Perform Formal Test process (see figure below). Consider which of the five

subprocesses (Hold Pretest Meeting, Execute Test, Determine Disposition of Incidents,

Hold Posttest Meeting, or Write Test Report) you are currently performing. I suspect

that, in the environment I've postulated, your group is only performing the Execute

Test and Determine Disposition of Incidents subprocesses. It would not be difficult

to start holding pretest and posttest meetings, and these could markedly improve

your process. At the pretest meeting, you should ask the developer to describe

the unit and integration testing performed and to identify areas of risk. The

personnel assigned to testing can then concentrate on these risk areas. In such

an environment, there probably hasn't been time to develop a test plan or test

design, but what would you base the plan or design on, anyway? Test cases or test

procedures will have been developed based on discussions with the developer and

the development team lead or manager. These can also be reviewed at the pretest

meeting for adequacy. This could turn out to be a long meeting for a complex application.

You might want to schedule a test-case and test-procedure review meeting prior

to the pretest meeting. Peer reviews of test documentation are always a good idea,

and the earlier they can be held, the better the return. As part of the

Perform Formal Test process, you should also make sure you have some sort of tool

or process in place to record defects discovered in testing, a process to present

them to the developers, a process to incorporate the fixes, and a process to regression-test

the application to make sure that the fixes work (and, perhaps equally important,

that they donŐt break something else).

The

Level 2 IPO diagram for process 1.4 illustrates the steps engineers must take

to prepare for testing, execute the test steps, handle incidents, determine success

or failure of the test, and write the formal test report.

|